Jan Pieńkowski, who died at the age of 85, was a quirky illustrator, writer and designer of pop-up books, whose Polish childhood and wartime refugee experiences fueled his fascinating work. He has published over 140 children’s books and portrayed the essence of his prodigious output simply by telling stories in pictures.

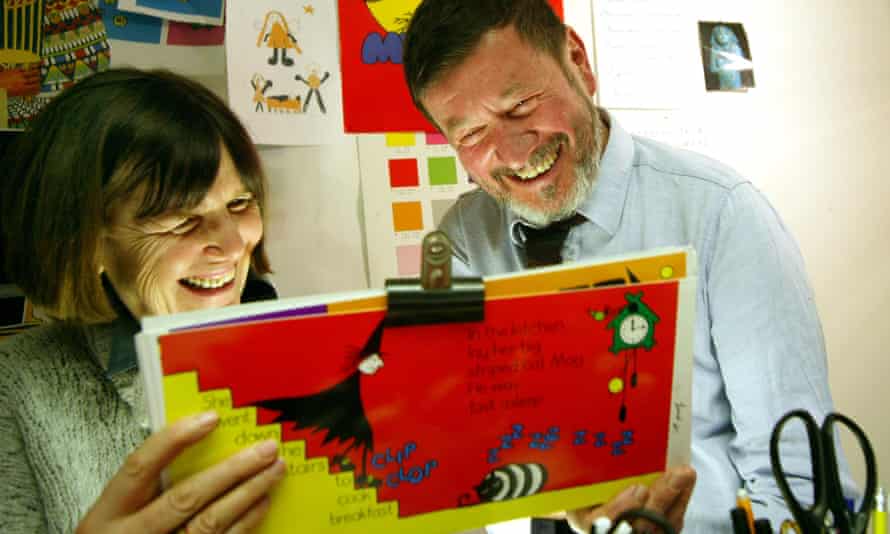

Pieńkowski’s characteristic style is immediately recognizable. For young readers, he worked in bright colors and used bold shapes. For older children, he often used a more varied palette with his colored ink washes as backgrounds on black paper cutouts. One of his most successful titles, working with writer Helen Nicoll from 1972 until his death in 2012, was Meg and Mog, an illustrated adventure series about a somewhat unfortunate witch and her striped cat. Pieńkowski said in an interview that Meg and Mog gave him the opportunity to use terrible monsters from his childhood and turn them into harmless toys.

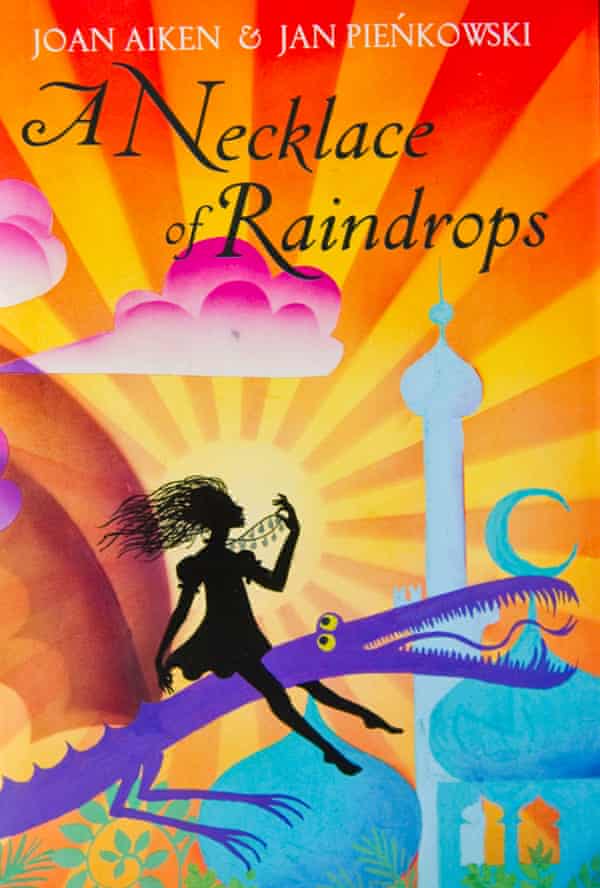

He won the Kate Greenaway Award in 1971 with writer Joan Aiken for their second collaboration, The kingdom under the sea. This was made up of the Eastern European fairy tales that were close to Pieńkowski’s heart and featured a first appearance of his beautiful silhouette illustrations. Their first collaboration was the equally delicately illustrated A necklace of raindrops (1968). His interest in cut-out papers, he said, stemmed from a wartime experience in an air-raid shelter in Warsaw, where a soldier amused the young Pieńkowski by cutting newspapers into wondrous shapes.

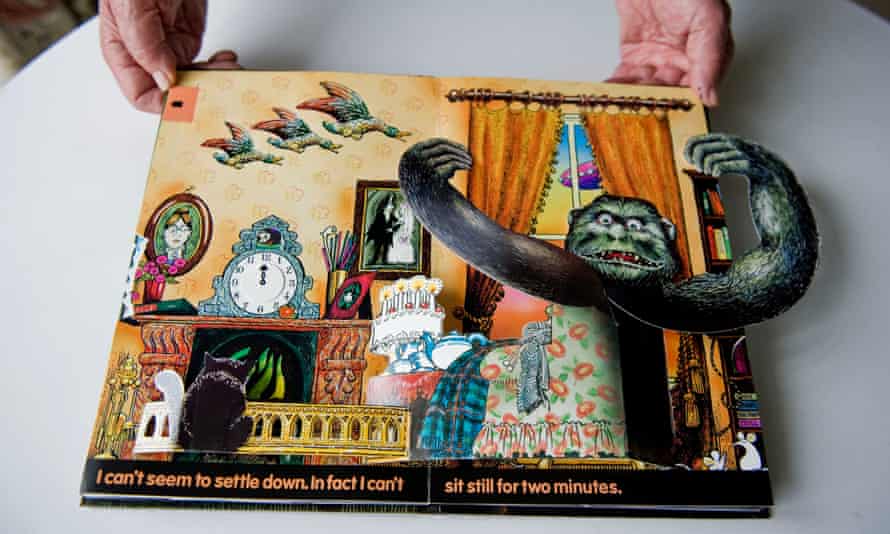

The masterful Haunted house Pieńkowski won his second Greenaway Award, in 1979. This delightfully creepy yet funny pop-up book changed what could be achieved through paper engineering and he continued to explore this genre with titles such as The Inventive and funny Robot (1981) and the thrilling Little Monsters (1986).

One or two reviewers questioned the creepy nature of many of his picture books, and he certainly had a leaning towards the macabre and gothic. Another source of inspiration for Pieńkowski was comics. As he put it, “The violence and hyperbole of Old Testament stories found an echo in Desperate Dan and Dennis the Menace. They too gave me my palette.He insisted that children like to be scared in a safe place, although he admitted that some Slavic folk tales are quite terrifying.

Born in Warsaw, Jan was the only child of Jerzy Pieńkowski, a pre-World War II field squire, and Wanda (née Garlicka), a scientist. It was while being cared for by a neighbor that Jan first learned of the terrifying tales of a Baba Yaga-like character. The woman told him “those totally unsuitable stories, get to a cliffhanger – and stop. I used to have terrible dreams, nightmares, of this witch, always chasing me and trying to put me in a pot…I think somehow she gave birth to Meg.

Rural life on a farm was interrupted, however, when the Nazis invaded Poland in 1939. The family moved to Warsaw, where her mother’s family lived, and her father worked briefly as a bailiff. When Jan was five, Jerzy, who had helped organize resistance groups, had to go into hiding for a year.

The family then left Warsaw and traveled through Europe, including Vienna, Italy and Germany, experiencing many ups and downs. They often lived in extremely harsh conditions, and for a time they were forced to sleep in pits under the train tracks. In 1946 they finally moved to Britain. Pieńkowski almost cracked when he recalled this period of his life on Desert Island Discs in 2009, saying the shrill sounds and screams still scared her.

As a young child, Pieńkowski was taught by his mother, who encouraged his passion for drawing and making things. Upon arriving in Britain, aged 10, he was sent to boarding school at Lucton in Herefordshire and added English to his already fluent German, Italian and Polish. Her passion for art grew further after she started nature drawing lessons at the age of 13.

When the family moved to London, he attended Cardinal Vaughan Memorial School in Holland Park, where he learned Latin and Greek, before going to King’s College, Cambridge, to study Classics and English. There he met Nicholas Tucker, a psychologist, critic and writer of children’s literature, and a lasting friendship began.

Although he was studying literature, Pieńkowski was already busy illustrating for Granta magazine and designing posters for university theater productions – thus developing a lifelong interest in stage design. Before Cambridge, Pieńkowski had spent a few months in Rome, one of his favorite cities, where he discovered opera. This love of the arts was a constant in his life.

Early in his career, Pieńkowski was employed to draw live on a BBC children’s show, Watch!, and it was through this work that he first met Nicoll, then producer of the episode. He has also worked in the design of book jackets, advertising and greeting cards.

After Nicoll’s death in 2012 he added more Meg and Mog titles with new stories written by his partner, david walser. Pieńkowski and Walser, a translator, artist, musician and writer, had been together for more than 40 years when they became civil partners in 2005 – as soon as it was possible – moving to Hammersmith, west London. A devout Catholic, Pieńkowski regrets not being able to have the union celebrated in church, although his priest says vespers for the couple.

He has produced several books on religious themes, such as The First Christmas (2014) and In the Beginning (2010), the latter featuring Walser’s masterful adaptations of the King James Bible. Other collaborations with Walser included a version of the original Nutcracker story by ETA Hoffmann (2008), The Glass Mountain: Tales from Poland (2016), and a picture book telling the story of Homer. The Odyssey (2019).

Pieńkowski was charming, good-natured and popular, with a touch of eccentricity. He was deeply attached to Britain and loved life in London, but still felt close to his homeland, spoke Polish and had many Polish friends. He used to pick up old discarded clothes and wear them – probably leftover from having had so little during the war years.

Never without a little black notebook, he never stopped drawing on the spot. In 2019, he received the Booktrust Lifetime Achievement Award.

He is survived by Walser.