For most of his life, French cartoonist Jean-Jacques Sempé, who died at the age of 89, put an end to public evocation of his chaotic and unhappy childhood. He was well over 80 when he finally admitted that the cheerful schoolboy character who would become his most famous creation – The little Nicolas – was a way of approaching a period of his life that he described as “a bit tragic”.

The adventures of little Nicolas and his gang of oddly-named friends, all firmly rooted in 1960s France, were “a way of revisiting the misery I endured growing up while making sure everything went smoothly. fine,” Sempé said. “You never get over your childhood. You try to fix things, to embellish your memories. But you never get over it.”

Far from dwelling on this misery, Sempé, as he signed his work and was widely known, was a man who, as Le Monde said, “could make the world laugh”.

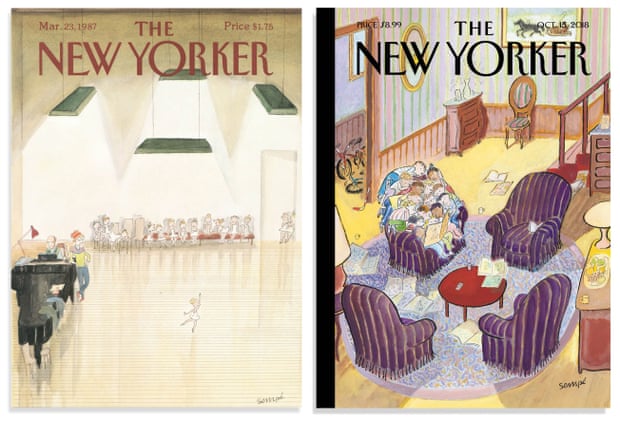

Celebrated in France as one of the country’s finest cartoonists, Sempé featured in many national publications but was largely unknown to the English-speaking world until The New Yorker commissioned him to produce a cartoon for its cover in the late 1970s. He subsequently produced 106 of the magazine’s covers, a figure unmatched by any other artist.

The adventures of Little Nicolas, the boy that Sempé created with René Goscinny, author of the Asterix series, has appeared in more than 30 languages, and was adapted into a feature film with Valérie Lemercier in 2009 (released in the United Kingdom in 2012 ) with a sequel in 2014. An animated film, Le Petit Nicolas – What are we waiting for to be happy (Little Nicholas – Happy As Can Be), won the Cristal for feature film at the Annecy Animation Film Festival in June and will be released in French cinemas in October.

“Le Petit Nicolas is timeless because when we created it, it was already out of fashion,” Sempé said.

Sempé was born in Pessac near Bordeaux in southwestern France, the result of his teenage mother Juliette Marsan’s affair with her boss while working as a secretary. Marsan gave her infant son to adoptive parents but took him back at the age of three to live with her and her new husband, Ulysse Sempé, a traveling salesman, who was an alcoholic. Jean-Jacques’ father-in-law, who sold anchovies and pickles on a bicycle, rode home from work passing through local bars, sparking inevitable quarrels that often ended in violence and flying dishes.

“There were always fights, always arguments, always debts and sudden moves… I lived with crazy people. They were completely crazy…my parents, poor people, they really did what they could. I don’t blame them for a second, they got away with it as best they could…”, confided Sempé to his biographer Marc Lecarpentier in 2019.

He dropped out of school at 14 – having already been away for the previous two years due to World War II – and then lied about his age to join the French army, later saying it was ” the only place that would give me a job”. and a bed. However, his short stint in the army was not glorious and he admitted that he had been confined to the barracks prison on more than one occasion for not paying enough attention while he was on duty or for other minor offences. When his real age was discovered, he was released and he moved permanently to Paris, where he would live for the rest of his life.

He was a lifelong jazz fan, having discovered French pianist and bandleader Ray Ventura, who helped popularize the genre in France, while listening to the radio at the age of six, then Duke Ellington, and dreamed of being a jazz pianist. Instead, Sempé began drawing at the age of 12, first small Mickey Mouse figurines, and continued throughout his teenage years, sending cartoons to be published in the local newspaper Sud. West while working with little enthusiasm or success as a door-to-door salesman delivering toothpaste. powder on his bike, then as a wine broker and personal valet.

In 1954, he met Goscinny – best known for having created the Asterix series with the artist Albert Uderzo – in the office of the Belgian weekly Le Moustique, which published their work. The couple befriends and begins to collaborate to produce cartoons of Little Nicolas.

“He [Goscinny] was my first Parisian friend… that is to say, my first friend,” Sempé would later say. “He made up a story in which the boy Nicolas recounted his life with his friends, who all had weird names… and we left. René had found the formula. The first story of Little Nicolas appeared in the Sunday edition of the South West in 1959, with the first book published in 1960 and four other volumes following.

In addition to his covers for The New Yorker, Sempé’s cartoons regularly appear full-page in Paris Match and other French national publications, including L’Express, Le Figaro, Le Nouvel Observateur (L’Obs), Le Parisian and Telerama.

An English edition of the Le Petit Nicolas series, translated by Anthea Bell, appeared in 1978. The books were republished in 2006 by Phaidon, who also published other English translations of Sempé’s books for the first time the same year, including

four collections of drawings covering his career: Nothing Is Simple (Rien n’est Simple, 1962), Everything Is Complicated (Tout Se Complique, 1963), Sunny Spells (Beau Temps, 1999) and Mixed Messages (Multiple Intentions, 2003). Phaidon said they introduced English readers to one of the “greatest cartoonists they ever know”.

The Paris-based British journalist John Lichfield, who interviewed Sempé in 2006 described him as the master of “panoramic cartooning”, drawing from high or distant vantage points and depicting rolling landscapes or elaborate cityscapes.

“I find the modern world difficult to draw,” Sempé told Lichfield. “Even when I draw computers, my friends point out that these are the types of computers that disappeared in the 1970s. To me the modern world lacks charm. I’m not saying things were always better in the past. They weren’t. But things seemed better to me, or at least more interesting…” What is important in a cartoon, he explains, is to “capture the essence of something , not to try to copy it”.

Sempé loved Paris and was a familiar face at renowned Left Bank establishments such as Lipp Brewery and Flora Coffee near his home in St-Germain-des-Près in the 6th arrondissement, where he counted among his friends members of the city’s intellectual beau monde including Françoise Sagan, Jacques Tati, Jacques Prévert and Simone Signoret.

In 2018, Sempé was named in the Panama Papers as having an offshore company, triggering a French tax investigation into his affairs.

Sempé died six days before his 90th birthday. Like his most famous creation, in his head he was forever young. “I’ve been known to be sensitive at times, but never adult,” he said.

Two marriages ended in divorce. He is survived by his third wife, Martine Gossieaux, whom he married in 2017; and by a girl, Inga, from his second marriage, to Mette Ivers. A son, Jean-Nicolas, from his first marriage to Christine Courtois, died before him.