Earlier this month, former Talking Heads frontman and oversized workwear pioneer David Byrne celebrated his 70th birthday, so it looks like the time has come for him to release a book that sounds pretty ambitious: “A History of the World”.

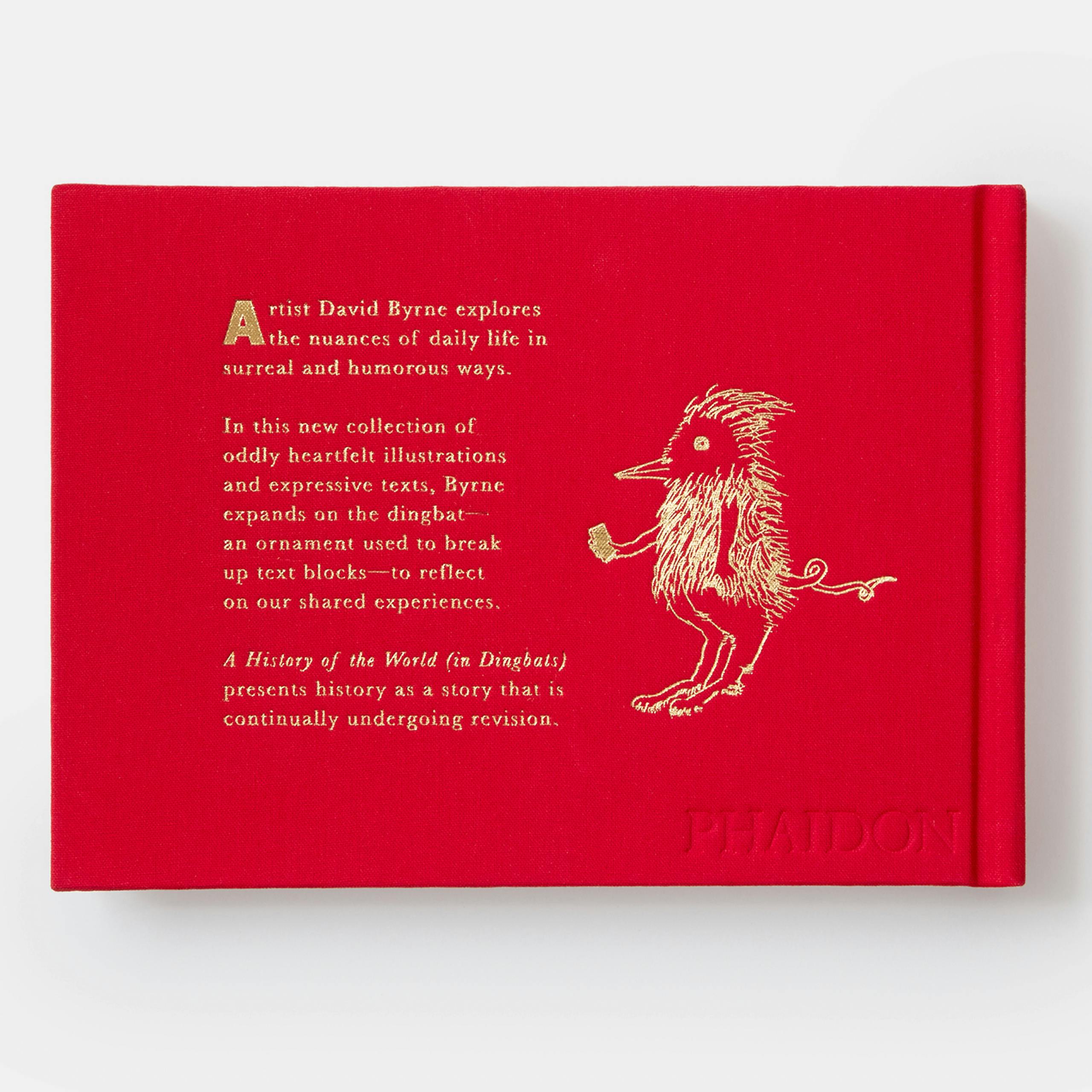

However, like most things Byrne, there’s a twist: it’s a world story (in Dingbats). The presentation of the book is as noble as its title: designed and edited by Alex Kalman, the bright red fabric jacket and gold embossing on the cover give it a sense of gravity and tradition, as if it adorns the shelves. For years.

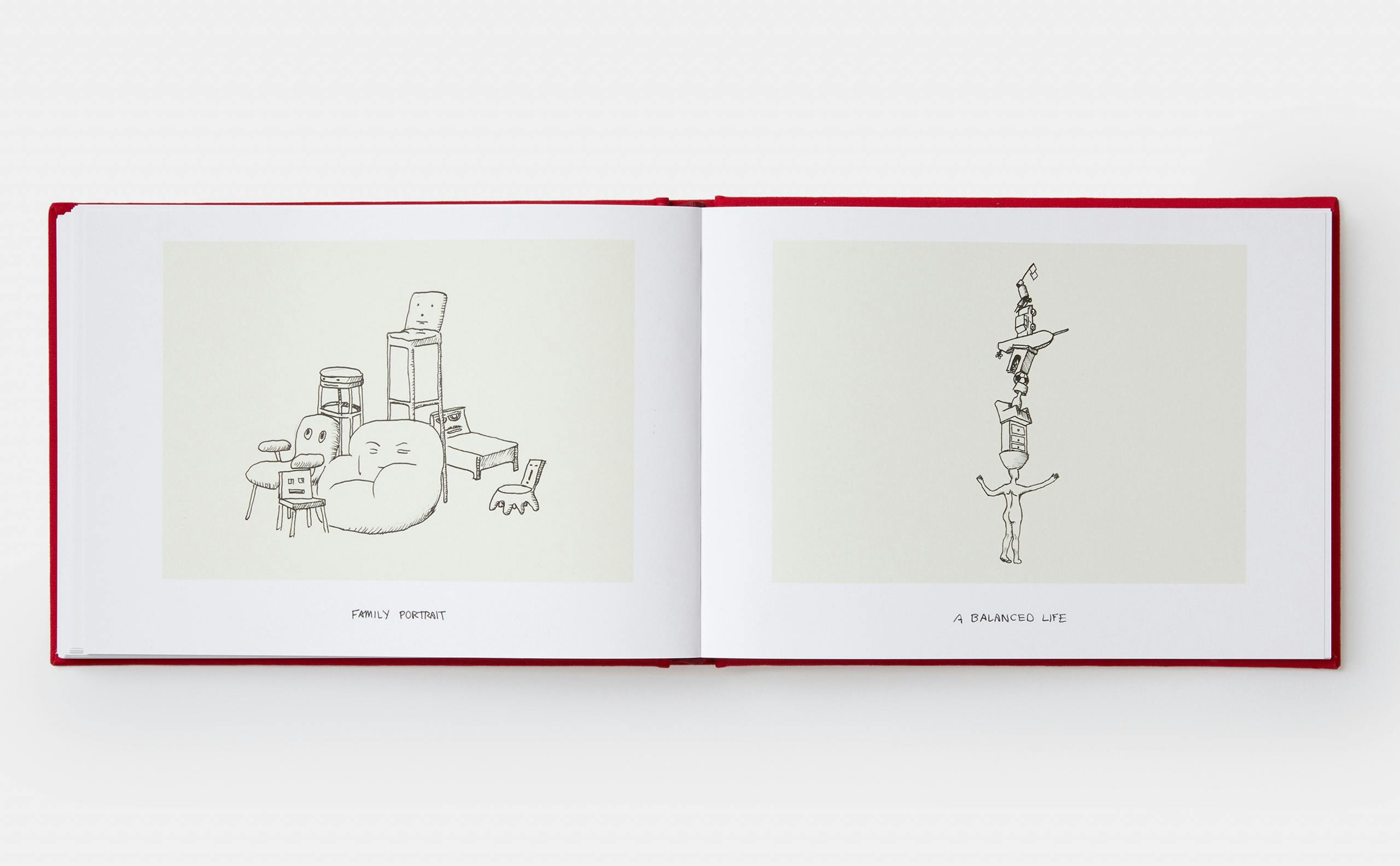

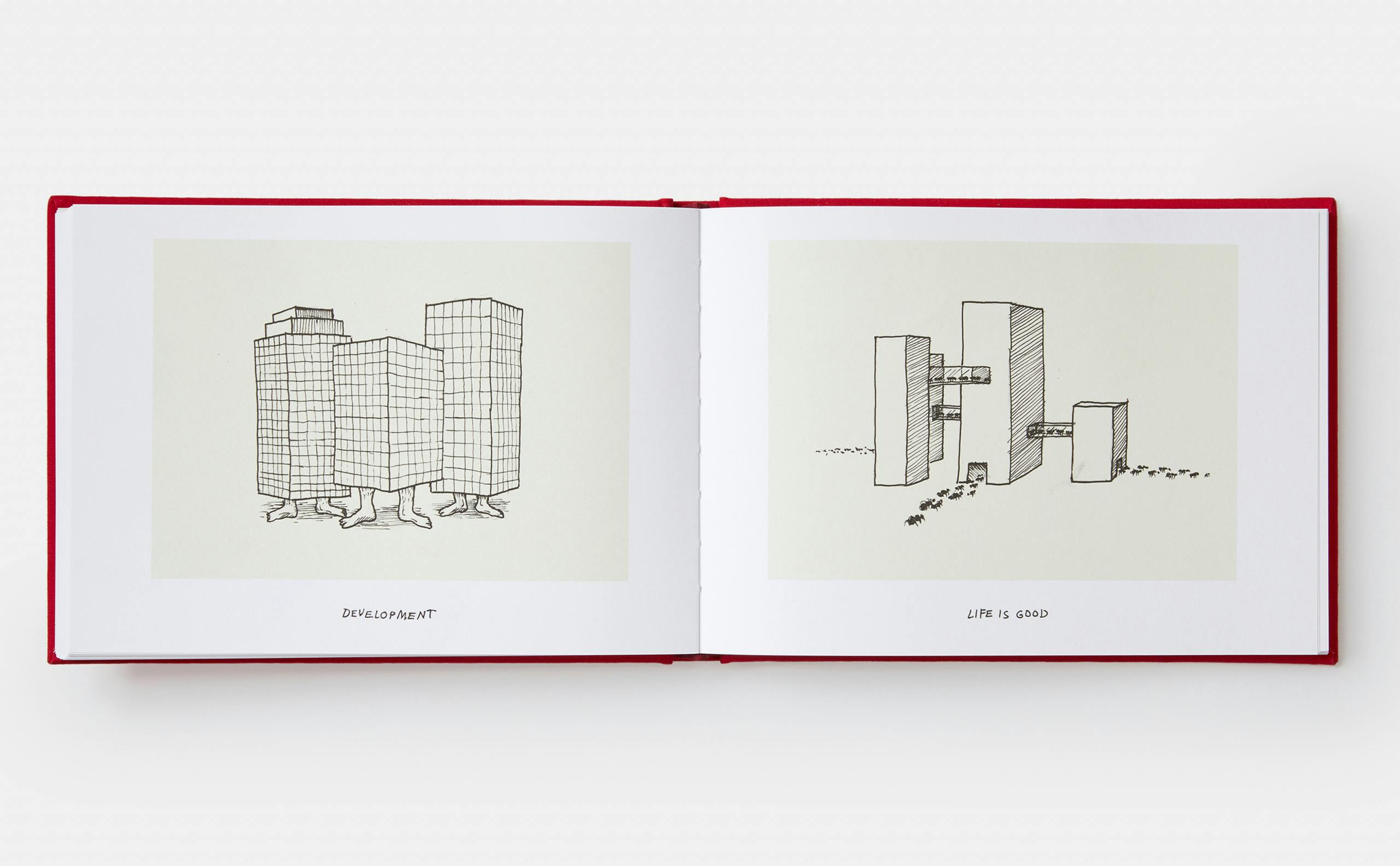

Does it present a history of the world? In a way, yes — but in the way we generally think of “stories”, not really. Is it important? Of course not. A History of the World (in Dingbats) features Byrne’s beautifully naive drawings, many of which offer succinct visual puns that evoke everything from that perennially fashionable term, “immersive” (the image for this shows a small man dwarfed by massive earphones – a gentle jibe at the word’s often infuriating omnipresence, perhaps) to the unplayable music (exemplified by a knot of horns and violins) to cheeses and in a modern state, in an image of box-shaped towers connected by depressing tubes and surrounded by Dalí-style ants.

These illustrations are punctuated by excerpts from Byrne’s verse, which often feels very Talking Heads-ish in both theme and phrasing: a page opens “We live in a city in our heads, the buildings that surround, as well as our clothes and hairstyles, we invented these things.” For nerdier-leaning readers, this will no doubt leave a mashup of The city of Dreams and Don’t worry about the government buzzing around your head – maybe with the line on the “so many times now” hairstyle change from life in wartime thrown in for good measure.

The images themselves are simply rendered as black line drawings and are soft, surreal and often very funny – reminiscent of David Lynch. simple parts based on linesand David Shrigley brilliantly weird visual one-liners.

Adding ‘dingbats’ in the title may confuse dingbats and graphic designers. But in the introduction to the book, Byrne begins with the connotations of the word “a stupid person”, before explaining its definition as “a meaningless typographical element – nonsense symbols used by composers long ago at a time to give layout instructions to a printer (a person, not a machine) and to create visual respite in a typographic layout”.

As Byrne points out, these evolved into a class of typefaces that came to include entire alphabets made up of illustrations of everything from household objects to Hello Kitty. David Carson reversed their historic use in an infamous layout design for an interview with Brian Ferry in Ray Gun, composing the entire piece in dingbats.

The illustrations were originally commissioned as a library of designs for an online magazine Reasons to be happy. But, says Byrne, “as soon as I started drawing I got carried away…they immediately took on a life of their own.” They were all created during the Covid-19 pandemic, and “a lot of times that mood comes back,” he writes.

As such, they came to illustrate “fears and longings…shared by so many others who have gone through and survived this surreal, tragic, eye-opening and unsettling experience.” That’s where the title’s “story” comes from: Byrne has come to see them as “a record, a story, of those changes” in people the pandemic has spawned. “I hope others will recognize themselves in some of these images,” he continues. “I guess like the songs, they’re not just about me.”

A history of the world (in dingbats) by David Byrne is published by Phaidon; phaidon.com